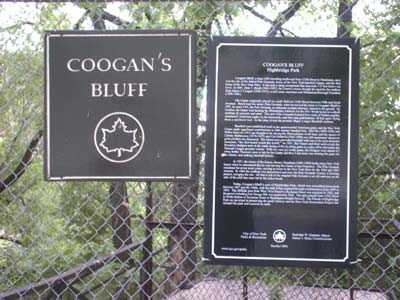

Text below is from the plaque

shown above

Image and text copied from http://www.projectballpark.org/history/nl/polo2.html

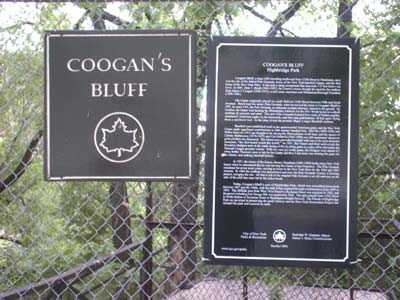

Text below is from the plaque

shown above

Image and text copied from http://www.projectballpark.org/history/nl/polo2.html

| COOGAN'S

BLUFF Highbridge Park (New York City) Coogan's Bluff, a large cliff extending northward from 155th Street in Manhattan, once was the site of the fabled Polo Grounds, home of the New York baseball Giants, and the first home of the New York Mets. It sits atop a steep escarpment that descends 175 feet below sea level. In 1891, John T. Brush (1845-1912), the Giants owner, bought the land for the stadium from James J. Coogan (1845-1915), a real estate merchant and Manhattan Borough President (1899-1901). The Giants originally played in a polo field on 111th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. Brush kept the name, Polo Grounds, when he moved the team to Coogan's Bluff in 1891. In April 1911, the Polo Grounds, an elaborate wooden structure, burned to the ground. By October, the Giants were hosting the Philadelphia Athletics for the 1911 World Series in a rebuilt stadium of concrete and steel. The new Polo Grounds boasted box seats of Italian marble, ornamental American eagles on the balustrade, and blue and gold banners, 30 feet apart, flying from a cantilever roof. At the time, it was the premier Major League Baseball stadium. Baseball soon established itself as the quintessential American game, and the New York Giants made significant contributions to 20th century baseball lore. Mel Ott (1909-1958) and Willie Mays (b.1931) are thought to be among the finest players of all time; and the names of Christy Mathewson (1878-1925) and Carl Hubbell (1903-1988) are still mentioned whenever great pitchers are discussed. The Giants also provided baseball with one of its most dramatic moments: "the shot heard round the world." In 1951, the Giants and their arch-rivals the Brooklyn Dodgers were in the ninth inning of the deciding game in a play-off to determine the National League pennant winner. With two outs left in the game, the Dodger were ahead 4-2 when Bobby Thomson came to bat for the Giants and hit a 3-run home run winning the game for the Giants, and making baseball history. In 1957, the owner of the Giants, Horace Stoneham (1903-1990) broke many New York hearts when he announced that he was moving the Giants to San Francisco. The Polo Grounds remained for seven more years, serving as home to the New York Mets for the 1962 and 1963 seasons. In 1964 the stadium was demolished and now the Polo Grounds Towers, a housing project, occupies the site. All that is left of the original Polo Grounds is an old staircase on the side of the cliff that once led to the ticket booth. Today, Coogan's Bluff is part of Highbridge Park, which was assembled piecemeal between 1867 and the 1960s, with the bulk being acquired through condemnation from 1895 to 1901. The cliffside area from West 181st Street to Dyckman Street was acquired in 1902, and the parcel including Fort George Hill was acquired in 1928. The park extends from 155th Street in North Harlem to Dyckman Street in Washington Heights/Inwood. The Friends of Highbridge Park are involved in preserving the park's history and the New York Restoration Project has cleaned the park and restored its trails. City of New York - Rudolph W. Giuliani, Mayor Parks & Recreaton - Henry J. Stern, Commissioner |

|

Relevant link: Polo Grounds New York Giants 1911-57,

New York Yankees 1913-22, MY HIGHBRIDGEMentions Eddie Grant Plaza ... Excellent link for some first-hand NYC history From Highbridge: "Da Bronx"

Information shown below in this section

is from

The following appeared in the NY Times Sept 30, 1957 A sad day at Coogan's Bluff. The New York Giants played--and lost--their last game at the Polo Grounds yesterday. Thousands of fans responded to the final melancholy out by chasing their California-bound idols to the clubhouse--and carrying away everything on the field that could be moved. The mass pursuit was touched off by affection, excitement, nostalgia, curiosity and annoyance at the fact the team next year will represent San Francisco. No psychologist, to say nothing of an ordinary lover of baseball, will ever be sure to what extent any one of these motives outweighed the others. But in their souvenir hunting, the enthusiasts at the final appearance of a once-great team in the shadow of Coogan's Bluff certainly did not stop at what was movable. Immediately after the Giants' last out at 4:35 P.M., the surging crowd caused the players to flee across center field as if they were running for their lives. Within a half hour the crowd had achieved, among other things, the following: Players Forced to Flee Ripped up the regular and warm-up home plates, the wooden base beneath the main plate, the pitcher's rubber, two of the bases and the foam rubber sheathing protecting outfielders who crashed into the center field fences. Those who rooted for the Giants to the bitter end also broke down and smashed the bullpen sun- shelter, gouged out patches of outfield grass, carried off telephones, signs and even telephone books- -and pried the bronze plaque off the Eddie Grant memorial monument in deepest center field. The plaque was subsequently retrieved from three youths by the police. All of this expression of last-ditch attachment came as a 9-1 loss to Pittsburgh wound up a baseball story dating to 1883. It was then that the New Yorks entered the National League, after inheriting the player roster of the defunct Troy, N.Y., team. By 1888--when the club won its first championship--it had acquired the name, Giants. Origin of Name Traced The original Polo Grounds was at 110th Street and Fifth Avenue--reputedly so named because the field was used by amateurs whose sport involved chukkers, rather than innings. After interim stays in Jersey City and Staten Island, the Giants moved to a hollow in Harlem that later became the parking lot for the present Polo Grounds, then used by a team in the rival Players League. In 1891 the Giants were rooted firmly in the "new" Polo Grounds--the name having moved from 110th Street, although the ponies and mallets hadn't. With the managership of John McGraw, beginning in 1902, their development into a national institution proceeded. From 1904 through 1954, the team won fifteen pennants and five world championships. The last was in 1954--twenty years after the passing of McGraw. Christy Mathewson was gone, too, and a galaxy of stars who had thrilled generations of boys and men had passed to the realm of the old- timer. Some of these, such as Rube Marquard and Larry Doyle, were on hand for the pre-game ceremonies yesterday. Others, such as Frank Frisch and Bill Terry and Mel Ott, were present only in the minds and hearts and conversation of others. An irony was that one of the greatest pre-game cheers went to a current member of the hated New York Yankees--Sal Maglie, a Giant until a few years ago. But in positive terms, there is no doubt that the last-day crowd's fancy centered on only one current Giant. He was Willie Mays, the wonderful Say-Hey Kid. Willie got two hits, but failed in his last two times at bat. When he grounded out in the ninth, a bleacher fan said: "Willie had of hit one, then the whole send-off would of been a success. Now it's a flop." But the fans, including the vandals, who converged in the square piece of ground bounded by the left and right field bleacher sidewalls, and the clubhouse, loved Willie just the same. They begged-- vainly--to see him and they even forgot their apparent bitterness at Horace Stoneham, the Giants owner, when they thought there was a chance of a final look at Willie. Stoneham was the butt of the harshest yells and chants. The fans seemed to think he personally had decided on the move to the Coast; and they didn't like it one bit. This may or may not have sharpened the determination with which the souvenir hunters went to work as the plunk of the ball in Frank Thomas' glove meant that the game, season and Giants' tenure at the Polo Grounds were over. After home plate had yielded to stubborn leverage, a group went to work on the four-inch wooden base to which the five-sided slab of white rubber was bolted. It yielded--as the sun sank lower and a touch of cool began to pervade the airy horseshoe. The base was carried away by a young woman who staggered under its weight. She said she was Helen Geotas, a teacher at the St. Andrew School of Greek American Culture at Beechurst, Queens. The pitcher's rubber--two feet long and six inches across--was uprooted and borne away in the subway by four youths who acknowledged on the way down town they had no idea what to do with it. Plaque is Recovered The Eddie Grant plaque--dating to 1921, three years after the former Giant infielder died as a hero in World War I--was gradually loosened and slid from its place by three boys of about 15. Its prompt recovery by police outside the field was a relief both to the club and to the Society of the 307th Infantry, which plans to remove the entire monument to a suitable new site. The orange-lettered green sign reading 484 FEET, just over the monument, at the deepest point of the field, was bent double. It was being yanked back and forth, and on the point of yielding, when guards intervened. Also taken were first and second bases; third was salvaged temporarily by a groundskeeper who said it had eventually been taken from him by an overwhelming group. Vinnie Smith, the second base umpire, scooped up the resin bag on the mound just in time. The wholesale pulling up of pieces of the turf gave rise to a number of whooping young Indians (not from Cleveland) running around with what looked like the scalps of victims with green hair. Others were content to scrape up handfuls of earth from the infield. Some had brought bags or cans to carry it lovingly away. The final game of the Giants' final season at the home they first occupied in 1891 drew a paid attendance of only 11,606. This is barely one-fifth of capacity. For the first six or seven innings, the fans behaved as if the game itself were at least as important as the farewell occasion. They rooted for the most part for the home team--as if in gratitude for the thrills the Giants had provided over more than half a century. But as the sun sank over the stands and shadows spread over the field, the crowd grew fidgety. The Giants were losing, 8-1, at the end of eight innings. When at the top of the ninth, the announcer, Jim Gorey, repeated the usual admonition about fans remaining in the stands until the players and umpires had reached their dressing rooms, a boo swept the stands like a cold wind in autumn foliage. The visiting Pittsburgh Pirates added a ninth run in their half and the Giant era--of McGraw and Mathewson and the lesser stars--was down to its last three outs. It took Bob Friend, the Pirate pitcher, just twelve throws to finish it. Don Mueller flied to right on the second pitch, Mays grounded to the shortstop on the fourth pitch. Dusty Rhodes--the hero of a world series only three years ago--dragged it out to three balls and two strikes. Then he grounded to Dick Groat at short. Before the infielder's throw had reached first base, the fans were leaping the barriers and surging toward the Giant clubhouse. The players, with a good idea of what was coming, broke for the clubhouse as if, at the least, a winner's share of world series money depended on it. And most of the players made the stairway safely. Manager Bill Rigney and Mueller were the last of the big names to arrive. Rigney looked back at the crowd, puffing and shaking his head as would a puzzled man. The players having eluded them, the fans went to work on the field. In the crowd that cluttered the space between the left and right field bleacher sections, one youth held aloft one of the warm-up plates. Others arrived with their own particular spoils. Then, as Giant and Pirate players looked down from twelve heavily screened clubhouse windows, the chanting began. Banner's Message in Vain Under a big banner somewhat forlornly pleading, "STAY TEAM, STAY," in the right field section, the mob began: "We want Stoneham!" The crowd obviously didn't "want" him out of love; they blamed him for moving the team to the Coast. "We want Stoneham!" they insisted. Then, as if anyone might have misunderstood, they turned it into a little song: "We want Stoneham; We want Stoneham; We want Stoneham--with a rope around his neck!" Somehow, perhaps because it was obvious that Stoneham was not going to appear, the mood of the chanters altered. They forgot about the owner and began to demand to see the one player they were really proud of in the dismal sixth-place year of 1957: "We want Willie," they repeated, hundreds of voices being swelled by hundreds of others, as more fans arrived from the diamond. "We want Willie!" But Mays didn't appear on the clubhouse steps. The crowd was disappointed, but gradually it got the idea. In right field, some youngsters began breaking up the bullpen shelter into even smaller pieces. Officially, the last "fan" to leave the Polo Grounds was a woman: Mrs. Blanche S. McGraw. She had attended the Giant games at least three times a week when her husband, perhaps the greatest single figure in Giant history, managed the team. Her right eye moistened a little as she was asked what she remembered with the greatest joy at the Polo Grounds. "Why, Mr. McGraw winning pennants," she smiled. And which pennants? "All of them." McGraw won ten pennants with the club. To the extent that the end of the Giant era at the Polo Grounds was "historic," it may be apt to observe that in baseball, too, history repeats itself. And surely in terms of their performance in their last game here, the Giants were merely doing what they had done one day in April, 1891, when they lost the first four games in their new home to Boston. "From the outset," wrote the Times baseball reporter on April 25 of that year, "it was evident that the local club had lost heart. In the field, with one or two exceptions, they acted like men under the influence of a drug, and at the bat they failed to show any of their old-time hitting. "What's the matter with the Giants?" Sixty-six years and five months later, the question might still have been asked. And the paradoxical attitude of the fans might well be suggested by another ditty they sang beneath the clubhouse windows as the heat of the day waned and the stands darkened. To the tune of "The Farmer in the Dell," it went: "We hate to see you go, We hate to see you go, We hope to hell you never come back--We hate to see you go." |