The National D-Day Memorial

Bedford City, Virginia

National D-Day Memorial

Bedford City, Virginia

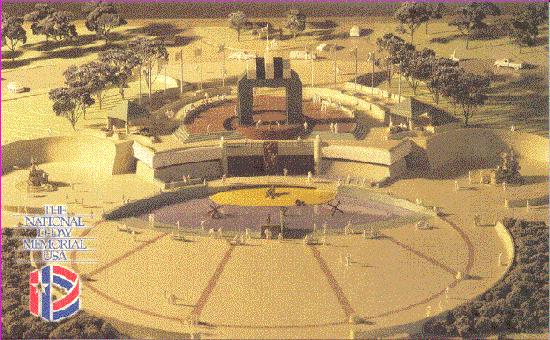

| The $13.6 million monument at the NATIONAL

D-DAY MEMORIAL in Bedford, paid for entirely by donations, sits on

88 acres of pastureland about 25 miles east of Roanoke.

The structure aims to evoke the Normandy landing with an architectural representation of a Higgins boat entering the small wading pool where sporadic sprays of water represent German fire. Overlord, code name for the invasion, is inscribed on a granite arch that stands 44 feet, 6 inches high representing June 6, 1944 and is colored black and white like Allied airplanes. Surrounding the arch are flags the countries that participated in the invasion: Britain, France, Australia, the Czech Republic, Belgium, Canada, Greece, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland and the United States |

AP Photo - 6 June 2001

Dedication of National D-Day Memorial

| THE WHITE HOUSE

Office of the Press Secretary (Bedford City, Virginia) For Immediate Release June 6, 2001 REMARKS BY THE PRESIDENT AT DEDICATION OF THE NATIONAL D-DAY MEMORIAL Bedford City, Virginia 1:10 P.M. EDT THE PRESIDENT: Thank you all very much. At ease. And be seated. Thank you for that warm welcome. Governor Gilmore, thank you so very much for your friendship and your leadership here in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Lt. Governor Hager and Attorney General Earley, thank you, as well, for your hospitality. I'm honored to be traveling today with Secretary Principi, Veterans Affairs Department. I'm honored to be traveling today with two fantastic United States Senators from the Commonwealth of Virginia, Senator Warner and Senator Allen. (Applause.) Congressman Goode and Goodlatte are here, as well. Thank you for your presence. The Ambassador from France -- it's a pleasure to see him, and thank you for your kind words. Delegate Putney, Chaplain Sessions, Bob Slaughter, Richard Burrow, distinguished guests, and my fellow Americans. I'm honored to be here today to dedicate this memorial. And this is a proud day for the people of Virginia, and for the people of the United States. I'm honored to share it with you, on behalf of millions of Americans. We have many World War II and D-Day veterans with us today, and we're honored by your presence. We appreciate your example, and thank you for coming. And let it be recorded we're joined by one of the most distinguished of them all -- a man who arrived at Normandy by glider with the 82nd Airborne Division; a man who serves America to this very hour. Please welcome Major General Strom Thurmond. (Applause.) You have raised a fitting memorial to D-Day, and you have put it in just the right place -- not on a battlefield of war, but in a small Virginia town, a place like so many others that we're home to the men an women who help liberate a continent. Our presence here, 57 years removed from that event, gives testimony to how much was gained and how much was lost. What was gained that first day was a beach, and then a village, and then a country. And in time, all of Western Europe would be freed from fascism and its armies. The achievement of Operation Overlord is nearly impossible to overstate, in its consequences for our own lives and the life of the world. Free societies in Europe can be traced to the first footprints on the first beach on June 6, 1944. What was lost on D-Day we can never measure and never forget. When the day was over, America and her allies had lost at least 2,500 of the bravest men ever to wear a uniform. Many thousands more would die on the days that followed. They scaled towering cliffs, looking straight up into enemy fire. They dropped into grassy fields sown with land mines. They overran machine gun nests hidden everywhere, punched through walls of barbed wire, overtook bunkers of concrete and steel. The great journalist Ernie Pyle said, "It seemed to me a pure miracle that we ever took the beach at all. The advantages were all theirs, the disadvantages all ours." "And yet," said Pyle, "we got on." A father and his son both fell during Operation Overlord. So did 33 pairs of brothers -- including a boy having the same name as his hometown, Bedford T. Hoback, and his brother Raymond. Their sister, Lucille, is with us today. She has recalled that Raymond was offered an early discharge for health reasons, but he turned it down. "He didn't want to leave his brother," she remembers. "He had come over with him and he was going to stay with him." Both were killed on D-Day. The only trace of Raymond Hoback was his Bible, found in the sand. Their mother asked that Bedford be laid to rest in France with Raymond, so that her sons might always be together. Perhaps some of you knew Gordon White, Sr. He died here just a few years ago, at the age of 95, the last living parent of a soldier who died on D-Day. His boy, Henry, loved his days on the family farm, and was especially fond of a workhorse named Major. Family members recall how Gordon just couldn't let go of Henry's old horse, and he never did. For 25 years after the war, Major was cherished by Gordon White as a last link to his son, and a link to another life. Upon this beautiful town fell the heaviest share of American losses on D-Day -- 19 men from a community of 3,200, four more afterwards. When people come here, it is important to see the town as the monument itself. Here were the images these soldiers carried with them, and the thought of when they were afraid. This is the place they left behind. And here was the life they dreamed of returning to. They did not yearn to be heroes. They yearned for those long summer nights again, and harvest time, and paydays. They wanted to see Mom and Dad again, and hold their sweethearts or wives, or for one young man who lived here, to see that baby girl born while he was away. Bedford has a special place in our history. But there were neighborhoods like these all over America, from the smallest villages to the greatest cities. Somehow they all produced a generation of young men and women who, on a date certain, gathered and advanced as one, and changed the course of history. Whatever it is about America that has given us such citizens, it is the greatest quality we have, and may it never leave us. In some ways, modern society is very different from the nation that the men and women of D-Day knew, and it is sometimes fashionable to take a cynical view of the world. But when the calendar reads the 6th of June, such opinions are better left unspoken. No one who has heard and read about the events of D-Day could possibly remain a cynic. Army Private Andy Rooney was there to survey the aftermath. A lifetime later he would write, "If you think the world is selfish and rotten, go to the cemetery at Colleville overlooking Omaha Beach. See what one group of men did for another on D-Day, June 6, 1944." Fifty-three hundred ships and landing craft; 1,500 tanks; 12,000 airplanes. But in the end, it came down to this: scared and brave kids by the thousands who kept fighting, and kept climbing, and carried out General Eisenhower's order of the day -- nothing short of complete victory. For us, nearly six decades later, the order of the day is gratitude. Today we give thanks for all that was gained on the beaches of Normandy. We remember what was lost, with respect, admiration and love. The great enemies of that era have vanished. And it is one of history's remarkable turns that so many young men from the new world would cross the sea to help liberate the old. Beyond the peaceful beaches and quiet cemeteries lies a Europe whole and free -- a continent of democratic governments and people more free and hopeful than ever before. This freedom and these hopes are what the heroes of D-day fought and died for. And these, in the end, are the greatest monuments of all to the sacrifices made that day. When I go to Europe next week, I will reaffirm the ties that bind our nations in a common destiny. These are the ties of friendship and hard experiences. They have seen our nations through a World War and a Cold War. Our shared values and experiences must guide us now in our continued partnership, and in leading the peaceful democratic revolution that continues to this day. We have learned that when there is conflict in Europe, America is affected, and cannot stand by. We have learned, as well, in the years since the war that America gains when Europe is united and peaceful. Fifty-seven years ago today, America and the nations of Europe formed a bond that has never been broken. And all of us incurred a debt that can never be repaid. Today, as America dedicates our D-Day Memorial, we pray that our country will always be worthy of the courage that delivered us from evil, and saved the free world. God bless America. And God bless the World War II generation. (Applause.) END 1:30 P.M. EDT |

![]()

| A memorial day article copied from

CBS NEWS

Online

Small Town, Big Sacrifice D-Day Wrung Young Life Out Of Bedford, Virginia BEDFORD, Virginia, May 28, 2001 (CBS) It was one of the greatest military operations ever mounted: D-Day. June 6, 1944. And the cost in human life was high. As many as 6,000 of the troops sent to drive Hitler from the continent died on the first day. And one small town, tucked into the Blue Ridge mountains of Virginia, paid the highest price. Bedford suffered the largest percentage of D-Day fatalities of any community in the nation. CBS News Correspondent Eric Engberg reports for Eye on America. ?We didn't hardly know how to speak to each other because we didn't know who was hurt. We didn't know who was dead.? A young schoolteacher in 1944, Ivy Lynn Hardy had been married to John Schenk for less than a year when word came that he was dead. A total of 19 Bedford boys in a single unit had been killed -- 19 from one town in one day. Recalls Hardy, "We would just meet each other and love each other a little." Bedford, in 1944, was a farm town of 3,200. It had a National Guard unit, chosen to be in the vanguard of the D-Day invasion. The 30 or so Bedford boys who made the landing trained in England with the rest of the 29th Division for a solid year. Their target was sector Dog Green of Omaha Beach. Lt. Ray Nance was wounded soon after reaching the beach. Recalls Nance, "My hands were all bleeding and they were oily from the boats being blown, and I got across, and I dug a hole in the sand with my hands, my bare hands." Roy Stevens and his twin brother, Ray, were in separate landing craft. Roy almost drowned when his sank short of the beach. Plucked from the water and sent back to England, he did not reach Normandy for four days. Says Roy Stevens, "I noticed there was working in a cemetery over there, and I see those little white crosses they started putting up The first grave I came to, the first cross, was my brother's. They had his dog tags up on the cross and a little piece of mud on it, and I kicked it off." Back in Bedford, weeks went by before loved ones got the sad news by War Department telegram. Lucille Boggess had two brothers in Company A, Bedford and Raymond. Both were killed. "It seemed like just a dark cloud hung over the community for a long time," she recalls. "It was just so traumatic, I guess, for the whole family. I remember hearing the fathers of the other men who died saying, 'I not only lost my son, but I lost my wife that day,' because a lot of women had a hard time coping with the loss." The next 6th of June, a memorial honoring the heroes of D-Day will be dedicated. Large in scope to match the courage of that day, it will be dedicated, appropriately, in Bedford, the little town which gave so much. |

![]()